Throwing the ultra poor into cruel darkness

Jester Mwale, from Kansonga Trading Centre in Ntchisi District has never lived in an electrified house. He only has that temporally luxury once in a while when he pays a visit to his affluent uncle who resides in the low-density Area 43 in Lilongwe City.

At 45 years, Mwale has always craved to live in an electrified house, but other circumstances do not allow him to have that comfort. He is among the 70.3 percent of Malawians that are considered poor in Malawi and in fact, he cannot afford to spend $1.90 (or K1 482) per day as an international definition of a poor person, according to the World Bank.

The share of the population below the national poverty line was estimated at 52 percent in 2016.

Mwale also finds himself in another category of a segment of the Malawi society that lives in darkness or simply does not have access to the national electricity grid. He is among the 89 percent of Malawians that sleep in darkness as the country only has 11 percent that is connected to the grid.

“I once tried to use solar products but I stopped because the products have now become expensive,” says Mwale. “With my unreliable source of income, I have reverted to using koloboyi [an improvised kerosene-powered lighting tin with a thread in the middle].”

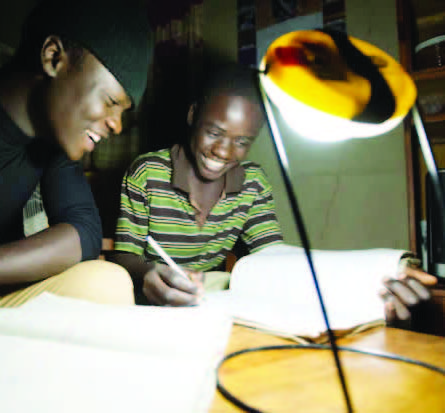

He recalls that at a time when he was using cheaper solar-powered lamps, life was easy as his Standard 7 daughter could study for a long time at night. However, Mwale’s daughter, who is now in Standard 8, has been forced to cut her study time because kerosene or paraffin is expensive and scarce.

Mwale, a farmer, is one of the many victims of a recent decision by government to classify some small solar lamps such as ‘bed-side or free-standing lamps,’ for new tax measures. Such lamps now attract an import duty of 30 percent and a standard value added tax (VAT) of 16.5 percent.

Before the new measures, the small portable solar-powered lamps—commonly imported by social enterprises and non-governmental organisations and are commonly known as pico-lamps or pico-lanterns—were a household item at Kansonga Trading Centre.

According to Mwale, people in his area preferred to use the pico-lamps because they were affordable and ‘saved them money’.

“A pico-lantern would help our children study at night. The lamp would also help our women go on with household chores at night.

“The lamp helped us to go outside to our pit-latrines at night and could light up the home the entire night,” he says.

Mwale says for businesspeople, the pico-lamp was a blessing. It enabled some to cook doughnuts at night so that early in the morning they had food for breakfast ready.

“The pico-lamp used to cost K7 500, but with the new VAT and import duty, it is now selling at K12 000,” he says, frustrated.

The leadership of the Renewable Energy Industries Association of Malawi (Reima) agrees with Mwale on the impact the new tax measures on pico-lamb have had on households in rural areas such as Kansonga.

The group decided to take to task officials from the Malawi Revenue Authority (MRA) and Malawi Bureau of Standards (MBS) to explain the tariff regime change.

The group also said contrary to the existing tax policy in force which zero-rates import duty, import excise and VAT on all imported renewable energy products, MRA is still taxing the products thereby suffocating the industry players and also throwing the likes of Mwale into darkness.

In the 2019/20 National Budget, government announced tax incentives for solar lighting products and other renewable by scrapping off duty, excise and VAT. The aim was to make solar lights affordable and accessible to Malawians as only around 10 percent of the population are connected to the grid.

Introduction of such a new tax measure pertained to solar panels, solar batteries, solar inverters, solar bulbs, solar regulators, solar chargers, solar accumulators, solar lamps, energy efficient bulbs, among others.

By announcing such tax incentives, government was also mindful of the fact that energy use is critical for physical and socio-economic development — both in rural and urban areas.

However, since September 2020, MRA, according to Reima, imposed tariffs on imported products, arguing that it was to do with change in tariff codes.

Environmental specialist Ian Dodkins, who is also business development manager for SunnyMoney, wonders why government has backtracked on its earlier decision.

He states that the move is retrogressive to the development of the country.

Dodkins’ firm, SunnyMoney is a social enterprise servicing ‘last mile’ communities in Malawi and supporting small Malawian entrepreneurs.

“With such tax on the products, the reality is that the market for a lamp of such a price now no longer exists in the hard-to-reach and low income rural areas,” he says.

“That villager in Chikwawa won’t even be approached to buy such an expensive small lamp. These pico-lanterns lamps have stands because they have been specifically designed to help with education in the home,” adds.

Reiama executive director Ron Kabvina also shares his concerns, recalling that since the removal of duty, excise and VAT in 2019, distributors had been importing and clearing solar lamps without taxes while trickling the benefits to the masses through reduced prices.

“But with the new tax measures, we now have distributors of these solar energy products who have their products in MRA warehouses for over seven months just because the tariffs changed without notice.

“The implication of this is that products such as lamps will have to cost 50 percent more as importers or distributors will have to factor in tax element,” he explains.

Some companies dealing with solar products or renewable energy products have repeatedly indicated that they are not against the clearance or tariff codes but have pleaded with MRA to include such new codes in the duty and VAT- free status.

Reacting to the concerns, an MRA official from Customs and Excise Division (Technical) Ephraim Munthali, who was present during a renewable energy stakeholders meeting at Crossroads Hotel in Lilongwe in February explained that some tariff codes had changed since the country’s migration to the Common Market and Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa) in 2018.

“As a way forward, I suggest that you write Treasury and specifically mention about the change in the codes from 94054030 to 94052030.

“This issue is hinging on duty rates other than tax classification. Classification is the mandate of MRA but in terms of duty rates, that is the duty of Treasury,” says Munthali.

But as the blame game rages on, policy analyst Alex Nkosi reminds government that increasing access to energy is a fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number seven.

SDG7 aims at “ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services by 2030, increasing substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030 and doubling the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency by 2030.”

The country’s National Energy Policy of 2018 also seeks to establish a vibrant, reliable, incentivised and sustainable private sector-driven renewable energy technology industry, among other broad objectives.

At the 27th Africa-France Summit, which took place in Mali in 2017, African governments, including Malawi, were encouraged to integrate solar technologies into their respective national electrification strategies.

But as the elephants keep on fighting, it is now the grass—the poor and helpless people like Mwale—who are suffering.

“We want the new Tonse Alliance government to relook into the issue of taxing solar energy if we are to have light back in our homes,” pleads Mwale.